There is some pretty dramatic stuff happening within the fossil fuel industries these days; low oil prices, profit loss, canceled projects and downsizing — to name a few. In this blog, I’ll unpack just a small bit of what’s going on, but the longer story is all germane to the divestment discourse. Before I get started, I should say that this post was inspired by a recent Financial Times article — one of the world’s leading [right wing] business newspapers. The article, an important indicator itself, was exploring the very real potential of a structural downfall for fossil fuels. Let’s dive in…

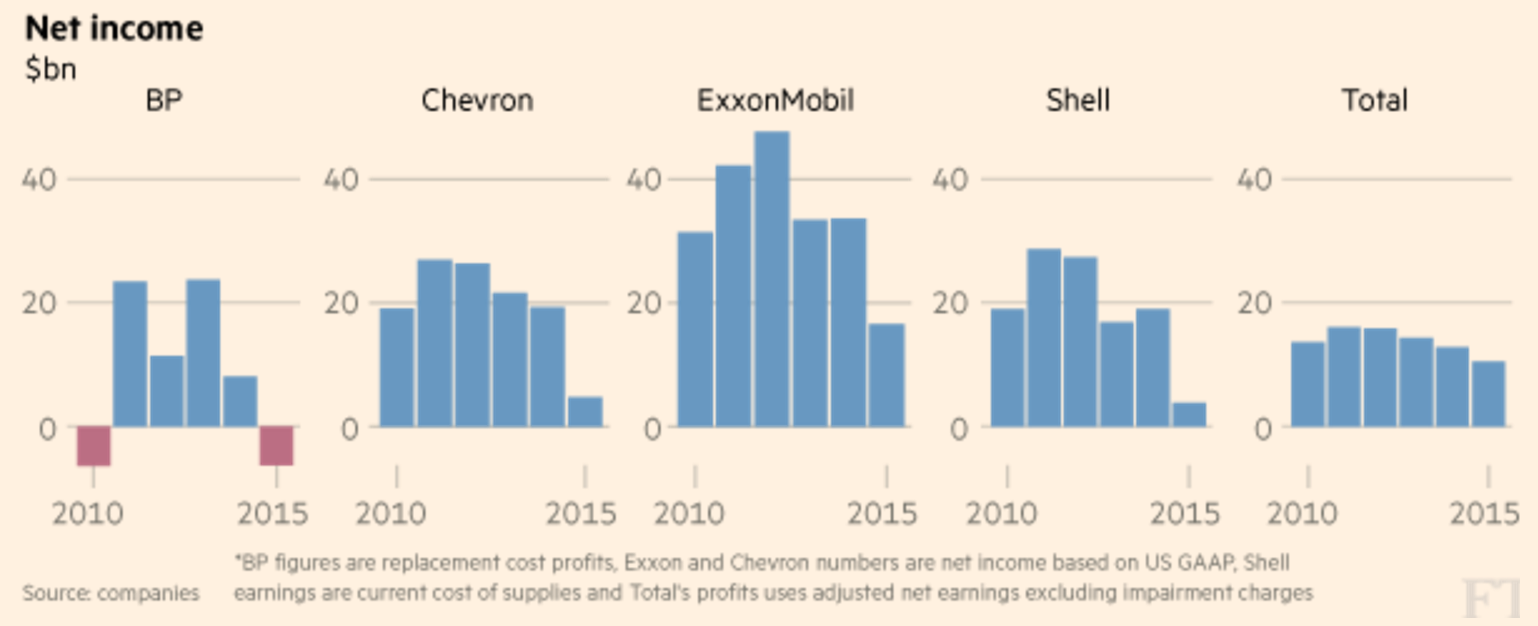

You already know, the coal, oil and gas industries are suffering. Across the board, from coal mining to Big Oil, fossil fuels (or the Energy Sector) is the worst performing and most volatile sector over the last five years. But, as you would expect, there is a desperate optimism coming directly from the industry.

When executives from the large oil companies and energy analysts talk about the industry downturn, they tend to frame it as a “temporary condition,” and almost never discuss structural shifts — like climate change. This is big blunder number one. Most energy analysts, and all fossil fuel executives, remain blind to the shifting socio-political world as a result of climate change. It seems like they are only looking at graphs of historical business cycles or industry growth over the last half century, and simply projecting forward. As you can see, in the past, things have been up and down, but generally up…so that’s what we expect going forward.

Anyone who is really paying attention to the connection between fossil fuel companies, carbon in the atmosphere, and climate impact, knows there is a big road sign saying “deep economic change up ahead.”

Low Oil Prices:

Supply for oil is way UP. When supply increases, and demand doesn’t, price drops — simple economics. As the journalist, Antonia Juhasz, has started saying, the industry is now engaged in an intense game of chicken, who can cut production last. The sentiment amongst Oil States and companies is, we will cut production if everyone else does too, but we’re not going to step back alone and let someone else take our market share. Hence, drilling and pumping and digging are still full throttle, maintaining an over-supply problem for the foreseeable future.

There are a few other reasons why companies continue to increase production during this supply glut. For example, smaller oil frackers (shale companies) in the US took on huge amounts of debt to start their drilling projects. Now, because of low oil prices, they have to pump much more just to cover interest payments — which again adds to the problem of over-supply.

Job Loss:

While the oil continues to be sucked out of the ground, companies are attempting to make up for their lost revenue. They use phrases like “efficiency gains,” which really mean cutting jobs… by the thousands. The oil industry has cut and estimate of 250,000 jobs since the price per barrel dropped.

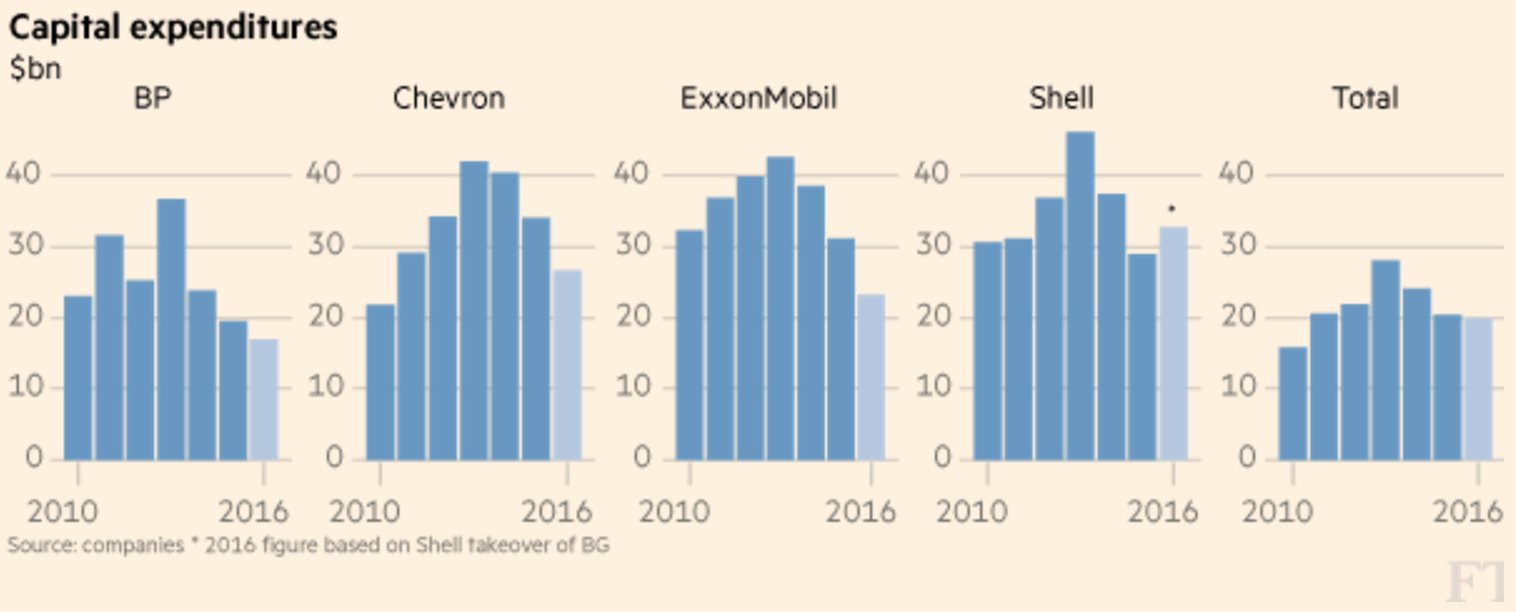

Canceled Projects:

In addition to cutting jobs, companies are reining in spending on finding and processing new reserves. This is a big part of the good news. According to the big banks that finance these billion dollar boondoggles, “just nine large projects, out of more than 230 awaiting a green light worldwide, [are] realistic candidates for approval this year.” We’re talking deepwater drilling, oil sands productions and the like. The Financial Times reported, “across the industry, some $400bn in expected investment has been canceled or delayed.”

Investors Reaction:

This is important because the stock market values of these companies are based off of the their future viability (projected profits). Standard & Poor’s, the credit rating agency [that participated in the 2008 financial crisis], just downgraded Chevron and Shell and said they would considering stripping Exxon of its crown status, AAA rating. A company called Canadian Oil Sands recently received a “junk” credit rating.

In fact, it should be noted that small and medium sized oil producers have less of a safety net than their bigger relatives, and provide a clearer picture of the industry invalidation. In 2013, there were 15 US oil and gas company bankruptcies. In 2015… there were 67.

What’s next:

If oil prices are low, why isn’t demand rising? Big Oil’s go-to argument is that energy demand will continue to rise and that fossil fuels are the only sources strong enough to fill that demand. Exxon wrote, “The big three fuels (coal, oil, gas) expected to meet 80% of the world’s energy needs through 2040.” Energy efficiency, electric vehicles, emissions mitigation policies, competitive renewable energy, and the big one, China’s weak economic growth combined with their commitment to reduce emissions, are all varying degrees of downward pressure on fossil fuel demand.

Outside of the fossil fuel industries’ wishful thinking, we know demand is dramatically and vehemently finite. We know this because, according to the world’s top scientists, so is our carbon budget. The question that no analysts or industry insiders dare to voice is whether or not big producers are taking the carbon budget seriously. Are the Saudis, for example, determined to sell as much of their carbon-based oil as they can, before we hit our carbon budget? Has an unspoken frenzy, a fire sale, to capture as much of the remaining market of fossil fuels begun? If so, this “game of chicken” is not about getting the market supply and demand back in balance. This is about who can survive for the longest in the end of an era. More of a Thunderdome than a game of chicken.

In short, this is an exciting time in energy economics. The final thought I’d like to posit is that the climate movement, and the divestment movement, continues to play a powerful role in moving this transition along. Thank you, campaigners and activists. You are real drivers of change.