The six dodgiest things we’ve uncovered about the oil giant’s influence on UK museums

By Danny Chivers, Art Not Oil

New report published today: BP’s cultural sponsorship: a corrupting influence

Fossil fuel companies have a long tradition of sponsoring the arts in order to promote their dirty brands and hide their climate misdeeds. By providing a trickle of cash to museums and galleries, oil, gas and coal companies aim to present themselves as responsible – even necessary – members of society. They’re trying to distract attention away from their real activities, such as, you know, pursuing a business plan for the end of the world.

In the UK, BP is the worst offender, having long-running deals with many of our most iconic arts institutions. This is bad enough. But now we have evidence that BP’s deals with public museums and galleries involve more than just slapping the company logo on the wall. It turns out that when BP says ‘jump’, museums often ask: ‘how high?’

A new report, released today by the Art Not Oil coalition, presents a sarcophagus-load of evidence gathered from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests over the last 18 months. It paints a wide-ranging picture of BP’s inappropriate influence over the institutions it sponsors, especially the British Museum, London Science Museum and National Portrait Gallery.

Here are six of the shadiest examples of BP-funded museums apparently compromising their independence in return for oil cash:

1) BP paid for a special Mexico-themed event at the British Museum – just when the company was bidding for lucrative oil leases in Mexico.

BP has an ongoing five-year sponsorship deal with the British Museum, but decided to hand over some additional cash for a Mexico-themed ’Days of the Dead‘ festival in collaboration with the Mexican Embassy in October 2015. The event allowed BP privileged access to Mexican government officials, just as the company was bidding for a slice of Mexico’s newly-privatised oil sector. The festival was pulled together by the Museum in around four months, a very short lead-in time for an event of this kind.

In other words, the museum suddenly decided to hold a lavish, last-minute Mexico-themed event at the very moment when it would be of maximum strategic benefit to its sponsor, BP. What a strange coincidence.

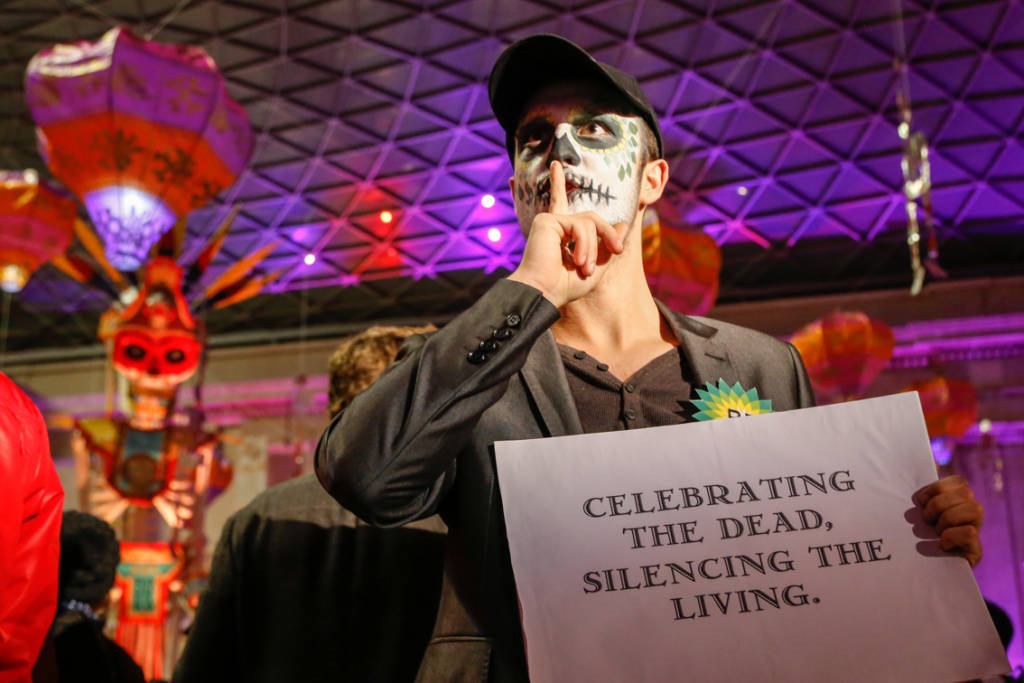

Protest performers gatecrash the British Museum’s BP-sponsored Days of the Dead festival,

attended by BP, British officials and the Mexican ambassador. Photo by Diana More

2) BP gets a say on the content of museum exhibitions

There’s a principle that museums are supposed to hold dear: commercial sponsors should never be allowed to influence the content of exhibitions. This concept of ’curatorial integrity‘ is a key part of museums’ ethical codes and widely felt to be a red line that must not be crossed. That’s why BP CEO Bob Dudley felt the need to state recently that BP’s arts funding comes with ‘no strings attached’, and why the British Museum told the Guardian: ‘Corporate partners of the British Museum do not have any influence over the content of our exhibitions.’

Except, uh oh – it looks like this may not be entirely true. Here’s what a British Museum staff member said in an email to BP, about a painting by a group of Indigenous women that was being considered for inclusion in a BP-sponsored exhibition:

‘We have heard back from the Spinifex women’s painters and they have confirmed they are not able to take on another commission at this point however we have been offered the opportunity to purchase one of their current works. The curator of the Australia exhibition is keen to move forward with this so we just wanted to make sure you had no objection to this?’

Yes, that’s right – the museum asked BP for permission before including a particular painting in the exhibition. That’s some serious blurring of the ‘curatorial integrity’ red line. This isn’t a one-off example either; the company has even publicly admitted to its influence over the Science Museum’s Energy Gallery, in a promotional article on its website – now removed – which stated ‘A BP advisory board headed by Peter Mather, BP head of country, UK, gathered 10 experts from BP in areas from solar energy to hydrocarbons to help with content for the exhibits.’

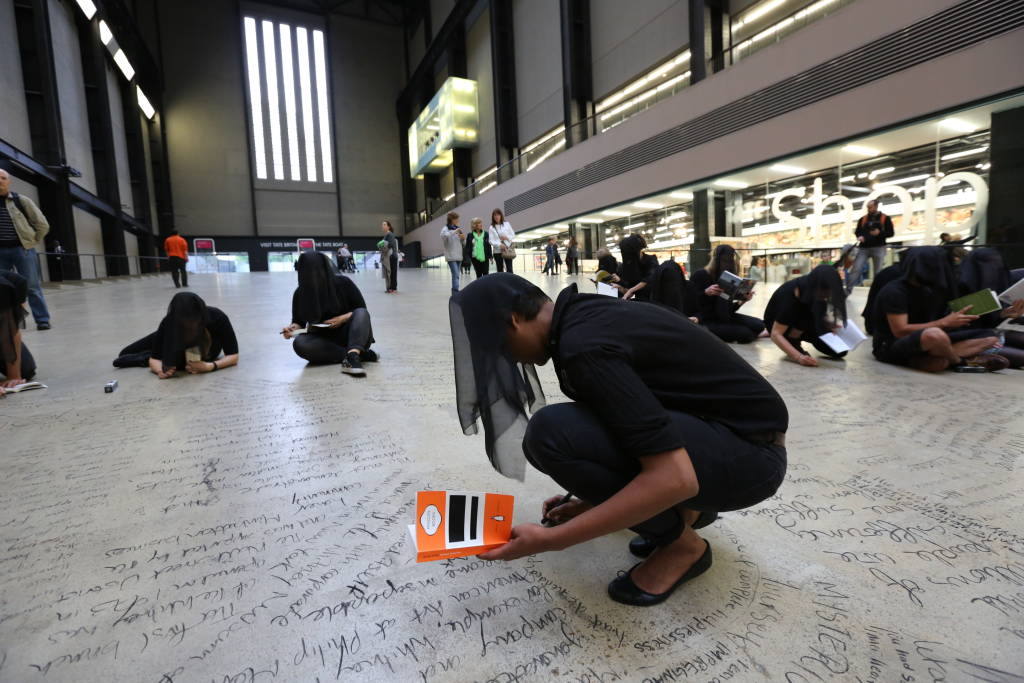

Theatrical activists ‘BP or not BP?’ hold a ‘rebel exhibition’ about BP inside the British Museum, without permission, in April 2016. See historyofbp.org. Photo by Amy Scaife.

3) BP works closely with museum and gallery security staff to discuss how to manage protests against its sponsorship

Far from being a hands-off sponsor, BP likes to roll up its sleeves and get involved in the day-to-day running of the places it sponsors – particularly when it comes to dealing with protests against its oily branding. BP hosted a special briefing session on protest management and training on counter-terrorism – the latter in partnership with the London Metropolitan police – for senior security staff from all the major London cultural institutions that it sponsors. Most of them seem to have attended, although they really haven’t been keen to share the notes from these meetings (see point 6).

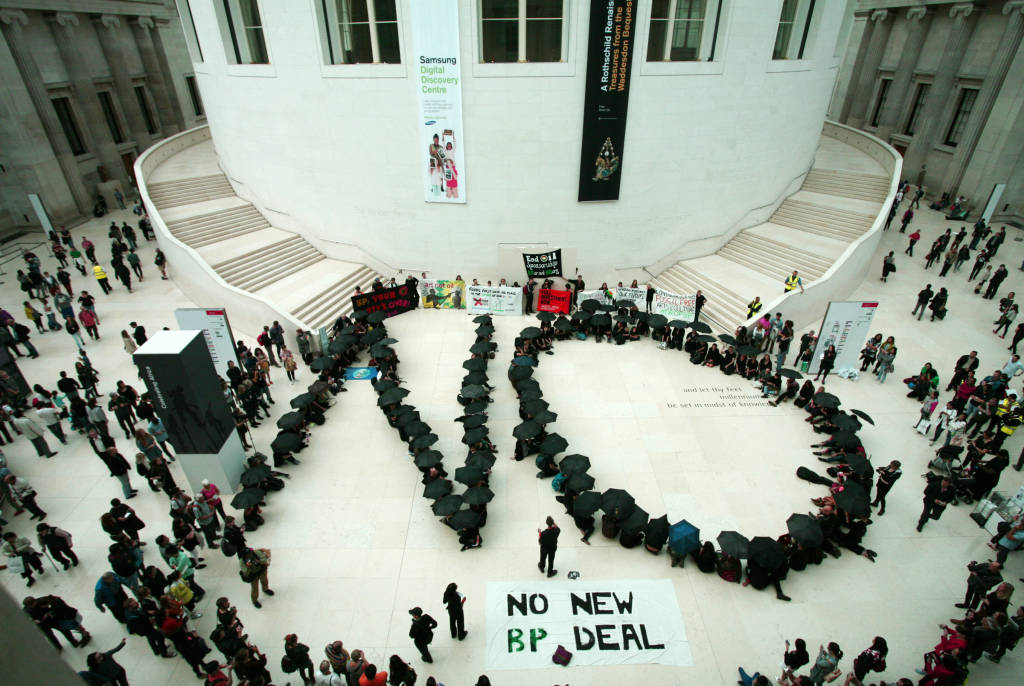

15 different groups create a day-long “protest festival” inside the British Museum, culminating in a 250-strong flashmob performance. September 2015, photo by Anna Branthwaite.

4) Many museum staff dislike BP, but don’t feel able to speak out publicly

An anonymous member of British Museum staff – speaking exclusively for our report – made their feelings about the sponsor clear:

‘It is generally known that of all the corporate funders, BP is the most unpleasant to deal with. They are extremely demanding of the Museum – bullying, I would say.’

The staff member also explained that it was not unusual for corporate funders like BP to demand that the museum organise special events and activities to suit their own needs:

‘The feeling from the majority of staff on events such as these is “why are we doing this”? It has nothing to do with our current exhibition programme, it hasn’t been factored into carefully considered longterm strategic planning for the public programme and it’s an enormous drain on resources for teams who already feel as though they are working over capacity. The feeling is one of dismay really, followed by a gritting of teeth and an attitude of “let’s get through this as painlessly as possible”. There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that the project is due to the whim of a funder, we have to deliver it and that we don’t have a choice in the matter.’

This may help to explain why a survey of British Museum staff by the PCS Union found that 66% of them agreed with the aims of the anti-BP protests. PCS represents 5,000 workers in UK museums and galleries, and the union’s cultural branch passed a motion last year to formally oppose oil (and arms) sponsorship in the institutions where their members work. When this happened, BP emailed its sponsored institutions to ask whether any of them had PCS members on their workforces, to which the National Portrait Gallery replied:

‘I believe the PCS Union does represent some gallery employees… I have shared this information with a wider group of colleagues so that we can be prepared and ready for any potential impacts.’

The union are not impressed with BP wading in like this. A spokesperson for PCS said:

‘It’s deeply troubling that BP either do have, or feel they have, so much influence. Staff, who are often low paid, have a legal and human right to join a trade union. It’s bad enough when that’s called into question by an employer, it’s sinister when it’s questioned by a corporate sponsor.’

Art Not Oil campaigners show their support for striking National Gallery workers on a PCS Union picket line. Photo by Art Not Oil.

5) BP selectively sponsors things that help it get more oil

We’ve already mentioned BP funding a special event that helped it score lucrative drilling rights from the Mexican government, but that’s not the only controversial project that the company has tried to smooth along via its sponsorship deals. In fact, the list of UK museum exhibitions that have featured the BP logo in the last few years is essentially a list of places where the company is trying to drill, often in the face of local opposition or in collusion with oppressive regimes. At the British Museum, the most recent BP-funded exhibitions have focused on China, Indigenous Australia, Mexico and now Egypt; at the Science Museum, BP sponsored an exhibition celebrating Russia’s achievements in space.

Curiously, these exhibitions are usually timed to coincide with a big PR push from BP in these countries, whether it’s trying to drill four ultra-deepwater oil wells in the Great Australian Bight (despite opposition from local people, Traditional Owners and their allies), forcing through gas projects in Egypt (with the military regime helpfully suppressing local protests), or building a partnership with the Russian state oil company Rosneft (with whom they are hoping to drill in the Arctic).

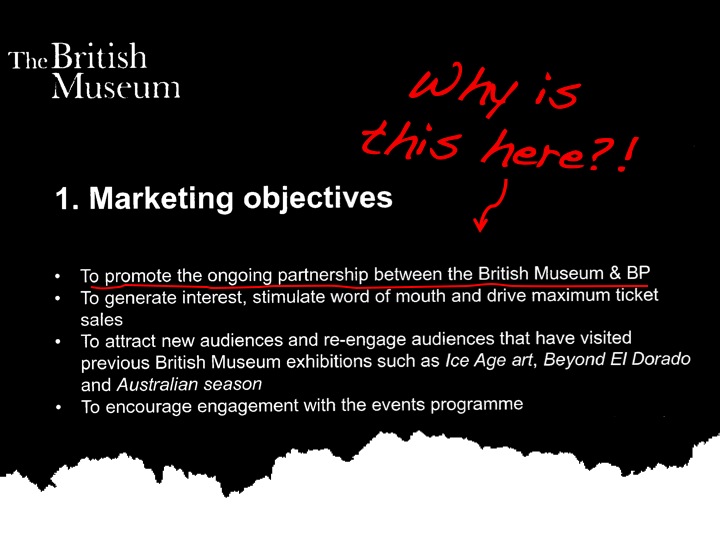

The sponsored institutions themselves don’t appear to have a problem with this; in fact, they seem happy to help. A slide from an internal presentation for the Indigenous Australia exhibition showed that the top marketing objective for the exhibition was ‘to promote the ongoing relationship between the British Museum and BP’.

It’s not just about overseas drilling rights either; sponsoring events at iconic cultural institutions gives BP privileged access to UK politicians and policymakers too. BP and the Science Museum even worked together on ’advocacy plans‘ for the 2015 General Election. Er, what?

6) We still only know a fraction of this story

The UK’s FOI Act only provides limited access to certain emails and documents, and they typically arrive with swathes of blacked-out text. The bulk of BP’s relationships with its ‘cultural partners’ – phone calls, personal conversations, and un-minuted meetings – remain hidden. There are unexplained gaps, contradictions and references that even raise questions about whether these institutions are following the FOI Act correctly.

All of this means that the Art Not Oil report reveals just the tip of the oil rig – but even this partial picture tells us that, despite Bob Dudley’s claims, BP sponsorship comes with all kinds of strings attached. We know that our arts institutions can survive without oil money – BP provides just 0.8% of the British Museum’s annual income, and both Tate and the Edinburgh International Festival have recently announced the end of their BP deals. It’s time for the rest of our cultural institutions to do the same.

Click here to read the full ‘BP’s Corrupting Influence’ report .

Join the global movement for #FossilFreeCulture! If you’re near London, join Art Not Oil’s ‘Fossil-Free Frankenstein Flashmob’ on May 18th at the BP-sponsored Royal Opera House ballet screening in Trafalgar Square. Or check out these organisations for actions and events near you:

Fossil Free Culture Netherlands

Stopp Oljesponsing Av Norsk Kulturliv