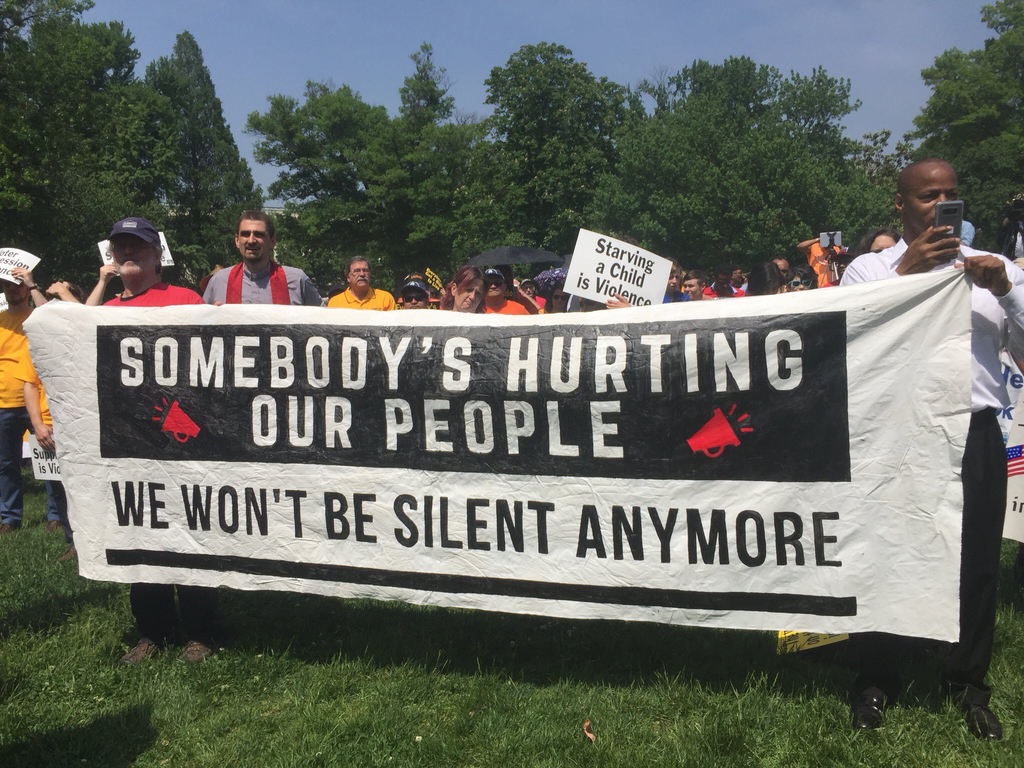

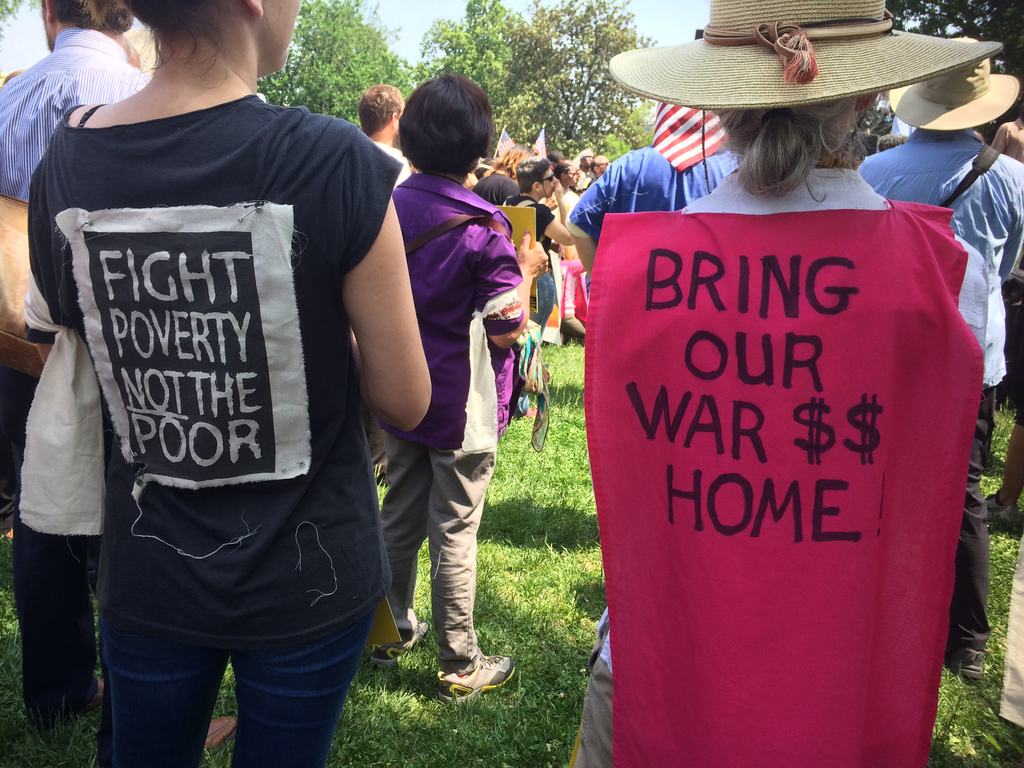

350.org recently endorsed the Poor People’s Campaign (PPC). The PPC is about drawing attention to the systemic inequalities poor people face, uniting them to challenge systems of oppression like racism, poverty, the war economy, ecological devastation and changing the narrative around poverty. The PPC launched on May 14th with a set of nonviolent direct actions, in which our Executive Director, May Boeve, participated. Those actions will continue for 40 days including the week of June 3-9th which will focus on the Right to Health and a Healthy Planet.

Personally, 350’s endorsement of PPC means a lot to me. Two years ago, just before I began working for 350.org, my Latino family went through really tough economic hardship. Both my partner and myself were unemployed. We went from being a lower middle class family to living on food stamps on the brink of losing our home. Watching my daughter live through the type of poverty and hardship I was accustomed to as a child was almost paralyzing. The anxiety and overwhelming feeling of helplessness that it brought to me was only outsized by the feeling of guilt I had for not being able to prevent her from also experiencing poverty.

I have experienced poverty throughout my life. Because of this experience, I believe the climate justice movement has the potential to create system wide changes that will ripple through existing systems of oppression — and break them. I’m originally from Guatemala, a country where more than half of the population lives under the global poverty line. To put it in perspective: that’s living on $1.90 US a day or less!

I didn’t spend all of my life in Guatemala. My family fled to Canada in the 1980’s. We left Guatemala because of the civil war, funded by US military intervention. Right-wing military dictatorships committed genocide against indigenous peoples, destroyed social movements, and deepened inequality. More resources and money were spent on the war economy than on the wellbeing of Guatemalans. The war made life impossible for us; to survive we left everything we knew.

The lasting effects of that civil war mean the few in power continue to maintain that stronghold, and the wealth that comes with it. The wealthiest 1% of Guatemalans own or control 65% of the wealth. Despite the fact that Guatemala has always been at the economic mercy of foreign powers, like the US and Spain, poverty in the country is linked to certain myths: including the idea that Indigenous and Black people are lazy, that our culture somehow prevents us from advancing in life, and that with just a little grit everyone can have a better future. Sound familiar?

If it does, it’s because many of the same poverty myths pervade the United States and Canada, two countries where I’ve experienced poverty. In Canada, I thought much of my experience deeply entrenched in poverty was because a refugee family of five led by a single dad, with only a grade 6 education, had many hurdles stacked against it. What I’ve learned as I’ve become more educated is that poverty isn’t a necessary evil. Families who face inequity and deep challenges can overcome those if there are welfare nets that both sustain families when they experience shocks, and that uplift them when they get caught in a circle of poverty. Poverty exists because the status-quo economic systems make it acceptable for the few to hoard the largest amount of wealth while the masses can barely get by. Currently in Canada the top 20% of Canadians own over 67% of the wealth and this gap continues to increase.

Life in Canada wasn’t easy, but my dad instilled the importance of education and working hard in all of us. In my experience, and in the experience of many working-class families, that idea means nothing when you are only one season of unemployment away from living under the poverty line, or have difficulty finding work in your own field.

In the US, my experience of poverty has been different, yet the same. How is it that my family went from being seemingly lower middle class to living under the poverty line? Simple: we have no wealth. We don’t come from wealth, and when we lost our jobs we lost our only source of income. Jobs with good wages and benefits in our field were scarce and hard to access. We ended up spending a year and a half looking for work and taking what we could get. In that time our unemployment benefits ran out, as did the little savings we had. It’s no coincidence that African Americans and Latinos are often in much more precarious financial situations than white Americans. In the United States, the unemployment rates for African Americans and Latinos have always been higher than the unemployment rate for whites.

At a time when poverty within countries is increasing, the United States’ huge wealth gap means 10% of the richest families own 3/4 of wealth — this is deeply segmented along racial lines. Add to this, the fact that existing welfare programs in the US do not put people above or on the poverty line. For our family of three, the federal poverty level is $20,780. We actually survived under that for the better part of a year and a half. After this experience of economic hardship and trauma, we are both gainfully employed and back on our feet more or less. It never escapes me that we are only another job loss away from ending up under the poverty line.

For those of us, like me, who were born in poverty and are part of the climate movement, the struggle is not just to save the planet – it’s to save ourselves from systems of oppression that allow a few to hoard wealth while the rest struggle to survive. For me, the climate justice movement has the most potential to have a system wide effect to not only care for the planet and move away from dirty energy, but also to make sure the fossil free transition is a just one for workers and communities. It’s my hope that this transition would not only move us away from fossil fuels, but also to a more equal society that dismantles systems of oppression which sustain the dirty fuel economy and the current capitalist system.